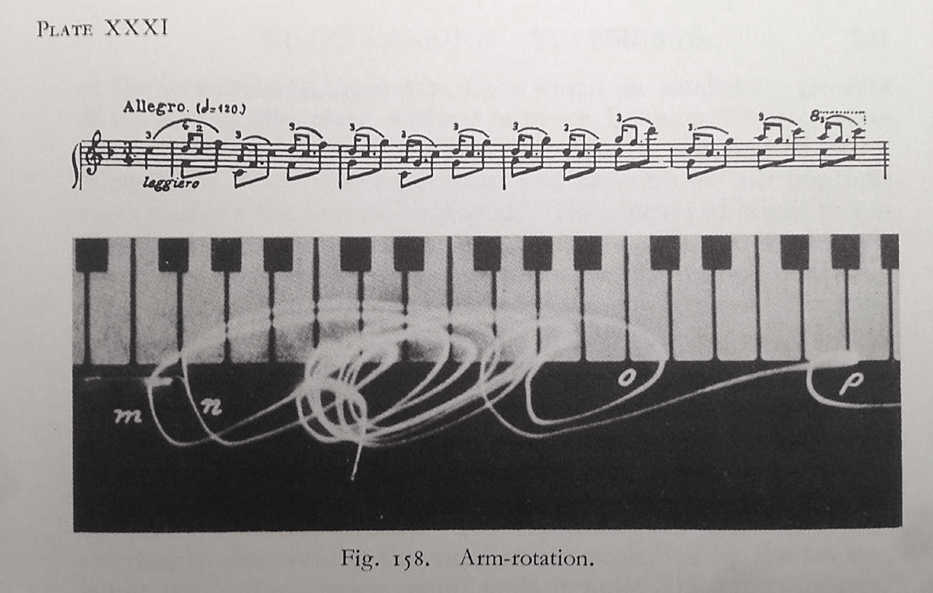

Parallels between Panistic and Artistic Techniques

Tom Philips (1997) observed that by the “virtue of its massive displacement of air… the grand piano can furnish a room and inform a space”, we can metaphorically view the instrument as a blank canvas for the art of music-making. A pianist must, therefore, have in his or her possession the tools and techniques necessary to create a ‘sound painting’.

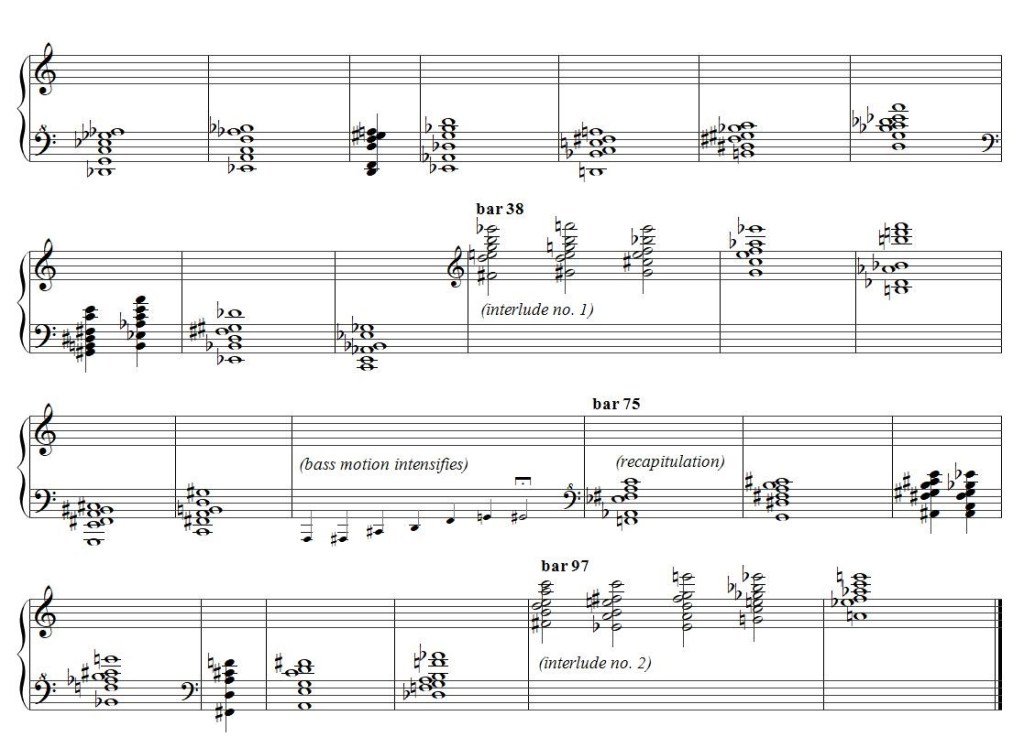

Cresswell’s Masterwork

Lyell Cresswell’s Piano Concerto No. 1 is New Zealand’s most recognised and successful concerto for piano and orchestra, and is one of, if not the Nation’s greatest concertante work. It is a composition that has received several live performances, two recordings, published scores and New Zealand’s most coveted prize for composition. This research project aims to uncover the underlying motivation and philosophical and technical approach of the composer through an in-depth analysis of the score, with reference to his life and artistic output.

New Zealand Piano Concertos

Within the realm of concert music, Coroiu (2022) noted that “[t]he instrumental concerto remains one of the most appreciated genres – by the general audience as well as by virtuoso interpreters…” (p. 49). It seems that there is something intrinsically attractive about pitting a star soloist against the power of a full orchestra. Indeed, among New Zealand’s National Orchestra’s seventeen concert programmes of 2025, ten contain a concertante work.

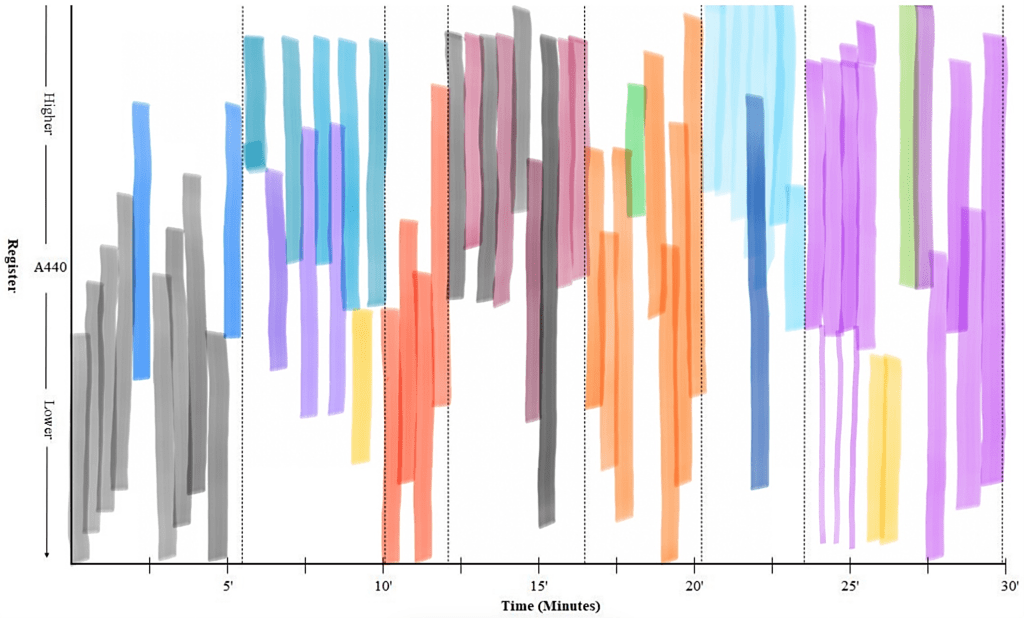

Concerto Arrangements for Chamber Ensembles

I discuss practical methods in which New Zealand concertante works could receive a ‘second life’ via live performances in arrangements for chamber ensembles.